What does a Narrative Department do?

“You write the story, right?”

Well, sort of.

The idea of a narrative department is still surprisingly new in the games industry. Even within development teams, there’s not a lot of knowledge about what people involved in narrative for games actually do and what they can do.

There is a general understanding that games writers write words, maybe for you to read, or maybe for other people to speak. There’s also a mysterious beast called a narrative designer, and people rarely agree on what that means. Even if you find two people with that job title, you’ll find that their jobs might be quite different.

I’ve attempted to write about the various things to do in game narrative before - there’s a detailed blog about it here. But let’s simplify it.

The narrative team fundamentally focuses on answering a few big questions for the player, which are all about game context.

Who am I?

Where am I?

What’s my aim?

What do I actually do?

How do I feel about it?

These questions are shared by the whole development team, but the narrative department cares about them. A lot. They have to understand the answers to those questions and then, critically, communicate them to the player… but also… communicate them to the team!

To expand on those a little:

A key narrative department skill is hiding under a ladder with a plastic toy whistle in your mouth. For Reasons.

Who am I?

Are you a detective? An embittered cop who’s close to the edge? A garden designer? An Italian plumber trying to rescue someone he really, really likes? What is the player fantasy? And what is their role in the game and in the game world?

This is something that the game developers need to figure out how to get across to the player. Does someone pop up and say “Welcome to the game, detective”? Is it subtler than that? Maybe you have a hat, a disorganized office, and a board covered in photographs and red string?

This is something that all departments will contribute to, but which the narrative team can deepen, add detail to, and document for the rest of the game team so that everyone can be involved in framing it for the player.

Games writers just need to accept that good communication doesn't need words. Also it's easier to localize!

Where am I?

Am I in a film noir world? A pulp adventure world, where archaeologists carry whips and wear hats? A world where everything is made of plastic bricks? What’s the setting? What does it feel like? How does it work? What’s the technology level like? Is gravity even a thing here? What mental model are we trying to give the player?

Here game writers and narrative designers will often collaborate with game designers and concept artists to figure out what the rules of the world are. How does it work? In a noir setting, if you get shot once, you’ll fall over and may need to find a doctor. In a pulp adventure world, you’ll be fine in no time, unless it’s a Dramatic Story Moment. Even if the rules are never explained directly to the player, the game team needs to know them so they can be consistent and make things feel solid and believable. There’s a lot of work here in examining players’ existing expectations and using their beliefs and biases. The more they already understand, the fewer explanations we need to give them.

But first, someone needs to write down all these rules-of-the-world so that the team knows them and can use them to bring the world to life!

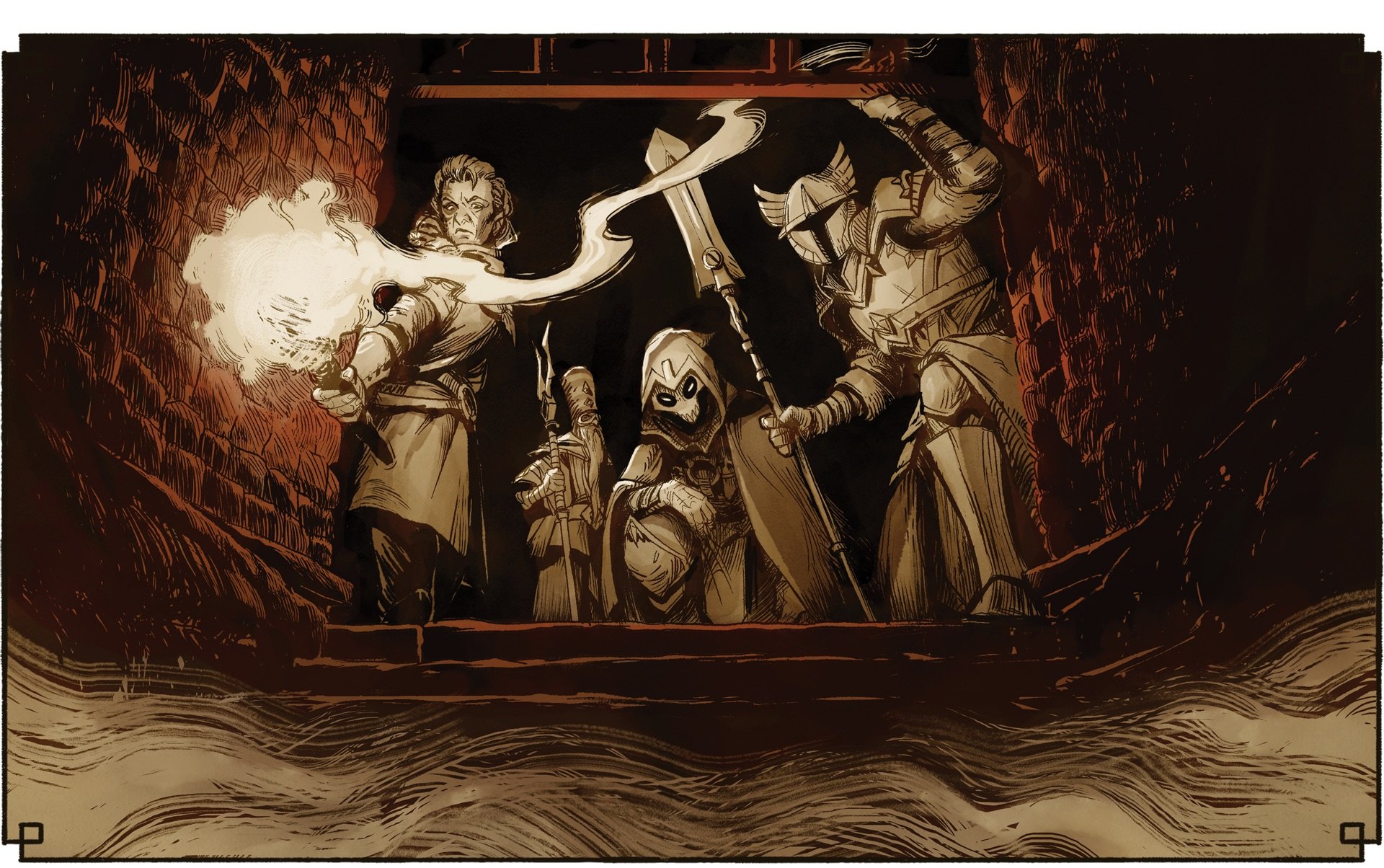

Communicating the setting and tone in a brief image. Art and narrative working together.

What’s my aim?

Why am I here? Am I a grizzled older person trying to protect a young person who might or might not be my child as we journey across a landscape filled with hostile creatures towards a vague destination? Am I just trying to run through mazes eating pieces of fruit and avoiding ghosts?

What should the player know and understand, when, and how do we tell them? Information delivery at key points so that the player understands the overall objectives and current objectives is, of course important. Signposting and direction is a major element of any game design.

But why should the player bother pursuing the aim? Just to get a trophy? The narrative department will help the player care about that aim, ideally connecting with them at a deeper level than that.

Once we know what we want them to care about, how do we - in all departments - actually make that happen? Dialogues between characters? Careful animation choices? Music? Appealing character design? A well-placed info-dump? The answer, as always, is ‘all of these,’ and the narrative team can help focus and marshal that.

This may also involve player choices, as we give them more than one aim to wrestle with and kick them hard in the feels about the choices they have to make.

What do I actually do?

Okay, I’m a detective, but how do I detect, exactly? By repeatedly pressing the A button? Ahah, I’m a silent assassin belonging to an ancient bloodline of assassins, am I? How come I keep getting in big unsubtle fights in marketplaces? Maybe if I shave my head and put on a black suit I’d be better at this stuff… Oh, I’m a smooth-talking Hero, right? How come I just shot a thousand people on my way to this cut scene?

There is lots of careful collaboration across departments on game mechanics - which, after all, in most cases, is the core loop and activity set of the game and is often thought about way before the story.

Do those mechanics really align with the player fantasy? If you’re a detective, then we’d better give you detective-type activities to do, and moments where you totally feel like a detective - “Ahah! I’ve solved the case!”

If the mechanics don’t support the fantasy, but the mechanics are fun and really what we want to build the game around - then maybe we need to change the fantasy!

If we’re adding new mechanics, how can we think about them through the lens of the player fantasy and the narrative, to make them support each other?

How do I feel about it?

I had to make a choice between Companion A, and Companion B, and have had to sacrifice Companion B. There’s lots of sad piano music playing. But he was a jerk anyway!

This really ties across all of the other questions, and again is a massive collaboration between departments. This often sparks character design, suggests how we build dialogue to create relationships between characters or the environment, provokes ideas about player choice and branching, and even informs game mechanic feedback.

And how we want the player to feel at any given point in the game is a critical question that we need to answer clearly, as then choices of music, sound, color palette, camera shot, speed of movement, background animation, available game mechanics (or withholding game mechanics) and everything else will combine together to provoke the player into feeling something that they will always remember.

We hope!

(Narrative Departments are built on hope.)

A Bonus Sidenote On AR, VR, and MR

Since it’s what we do here at Resolution, here are some things that are true about storytelling for a platform where players put on headsets and have characters appear in front of them in a physical space.

It’s not at all like cinema. Cinematic writing and acting won’t really work. There’s no possibility of close-ups on intense faces. We can’t point the camera at anything.

It’s often not like a computer game. Particularly not like the sort of blockbuster computer game that steals a lot of ideas from cinema. Game interactions, cut-scenes, and signposting often won’t work as you’d expect.

It’s most like a theatrical performance that’s happening all around you. Theatre cares about physical space and cares about getting emotional performances across to you from a distance. It also knows how to draw your attention so you look at particular things when they happen.

Actually, it’s often like LARP, too. You know. Dressing up as characters and acting as them in a physical space. Which we used to be called geeks for doing, but apparently it’s cool these days. Right? It is cool, isn’t it? *adjusts wizard’s hat and looks hopeful*

Anyway, thank you for your time.